Shame and Consciences

adapted by Mihangel

from Fathers of Men by E W Hornung

January 2005

Preface

My three-part Scholar's Tale was set at Yarborough School in my own day, which was long enough ago. This is another story about Yarborough, but set in the even more distant past, well beyond living memory. And it is not really my own work. What lies behind it demands a deplorably but necessarily long explanation.

Ernest William Hornung (1866-1921), the son of an émigré from Transylvania, was a prolific British novelist, befriended by Kipling and Wells and married to Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's sister. While he never quite matched his brother-in-law's success with Sherlock Holmes, he did create the equally memorable character of Raffles the gentleman crook, who has proved equally long-lived: almost all the Raffles books are still in print. But that is by the way. We are concerned not with them but with one of Hornung's later novels, Fathers of Men, published in 1912, reprinted only once in 1919, and now virtually forgotten. Its setting is the Yarborough School of 1880 to 1884, when Hornung himself was there as a boy.

Victorian school stories were almost two a penny, but few are memorable. Even Tom Brown's Schooldays, the best known and one of the better written, is populated by rather cardboard characters. Fathers of Men, it seems to me, has much deeper insights. Nor am I alone in this view. Hornung himself felt it his best work. His biographer Peter Rowland (Raffles and his Creator, 1999) tends to agree. Reviewers praised it highly: to quote two verdicts, it is "a fresh and penetrating study of that eternal problem -- the human boy," and it is "serious, compassionate, absorbing, and deeply intelligent." It seems well worth resurrecting.

None the less there are problems. The first half, with its leisurely setting of the scene, is undeniably slow. The second half, where the real action lies, does in places resort to the over-worn conventions of the genre, notably the stock figure of the untutored prodigy of a cricketer. In addition to that, the style can be horribly convoluted and wordy; to quote a not untypical sample, "The anxious submissiveness of the really good boy, with the subtle flattery conveyed by implicit obedience to an overbearing demand, had so far mollified the master; but Jan did not avail himself of the clemency extended." Verbosity of this kind hardly makes, these days, for easy reading.

But perhaps the biggest difficulty is that in Victorian times (as for long after) school stories, almost by definition, were wholesome and uplifting. Orthodoxy and prudery forbade any serious challenge to convention. Individual boys, then as now, undoubtedly questioned the accepted religious and moral code, but few dared question it in public. No more could novelists allow them to question it in print. And however well-observed the characterisation, whatever other complications might tangle their heroes' lives, these authors invariably left one unmentionable element unmentioned. They could not admit that boys were aware of, let alone preoccupied with, anything so sordid as sexuality. In that sense if in no other, their tales are neither whole nor real.

Why, then, resurrect this story on a gay site? The answer is intriguing. Hornung, though placidly married, was gay. There can be little doubt about it. As a grown man he befriended boys. The relationship between Raffles and his sidekick Bunny is latently homosexual. Hornung deeply admired Oscar Wilde. Indeed when he christened his only son, at the very moment of Wilde's downfall and disgrace, he gave him the name of Oscar. This was as clear a sign of his sympathies, and at the time almost as scandalous, as a father in 1945 naming his child Adolf.

What is more, it seems that Fathers of Men was originally neither orthodox nor "wholesome." Hornung sent an early draft for criticism to a close friend, who pounced on unspecified episodes and dialogue "which seemed likely to spoil the book." Hornung's arm was twisted, and he spent wretched months making the necessary changes. Many years later this same critic was praised by a third party for saving Hornung's reputation. The very guarded language in which all this is recorded strongly suggests that the offending passages were sexual in nature and, given the context, homosexual.

We will never know exactly how that early draft ran. But a few hints have survived the alterations; possibly, indeed, they were deliberately allowed to survive. These I have developed into a new thread, matched as best I can to the texture of the original and woven into the fabric of the tale at places where there seem to be obvious gaps. Because so revolutionary a topic, in those days, would hardly be picked out in too garish a shade of red, Hornung's expurgated thread was surely subdued in colour. So too, therefore, is my replacement thread. It is too much to expect it to follow the original pattern, but I hope that it may restore a touch of reality and wholeness to an otherwise good story.

On top of that, I have done a great deal of tinkering. Two complete chapters, which contribute nothing to the development of the plot or the characters, have gone by the board. Throughout, short passages have been added here and subtracted there. In particular, I have adjusted almost every sentence to make the style more simple and succinct. As a result the overall length has shrunk by a quarter, with the loss of no substance but, I hope, a gain in readability. But I have hardly touched the words which Hornung puts into the mouths of his characters. Such parlance as "I say, chaps, I had a jolly ripping time in the hols" may make present-day toes curl. But in it we hear the authentic voice of the Victorian public-school boy. A critic of the day, a teacher by trade, castigated standard school stories -- Tom Brown included -- because "no boys ever talked as their boys did," but he heaped praise on Hornung for "reproducing boys' talk as it actually is."

A word on the Headmaster's sermons. Hornung's apparent quotation from one in Chapter 30 is in fact of his own composition, but the extracts I have inserted into four other chapters are the genuine article, drawn from the old man's published works.

In short, I have tried to retain not only the essence of the story but its period flavour too; for it is, and it ought to remain, a period piece. This raises minor problems. Because education at places like Yarborough was dominated by the classics, there are constant references to Greek and Latin. There are snippets from current Gilbert and Sullivan songs. There is period slang and school slang which (except where it is too obscure) I have retained and sometimes explained. But such details are fine brush-strokes which hardly affect the overall picture: if they escape the reader who does not know Patience from Pinafore, or a dactyl from a spondee, it does not matter a hoot. What is more important is to steer clear of reading modern nuances into period language. The present-day connotations of "queer" and "gay" lay, at that time, far in the future. When a boy called someone "straight," he meant honest and honourable. A fag was no more than a junior boy doing menial jobs for a prefect. If, to the house-master, "boys are dearer than men or women," that did not make him a paedophile.

A greater difficulty for some non-British readers may be the cricket which looms large in the second half of the tale. Passing mentions of the long-departed Lillywhite's Cricketers' Annual and the still-surviving Wisden's Cricketers' Almanack can be taken in their stride. But there are whole pages of ball-by-ball commentary. Drastic pruning here would not only destroy a fascinating insight into the game at a time when there were only four balls to the over and serious bowlers could still bowl underarm lobs, but it would also spoil the story. I have therefore retained them. Here too a knowledge of the rules is not essential, but to those who wish to know more I once again commend the Seattle Cricket Club's website at http://www.seattlecricket.com, and especially its page on Explaining Cricket to Americans. And, after all, is not baseball derived from cricket?

The school's organisation, which may be another puzzle to non-Britons, deserves a word of explanation. It comprised three distinct groupings, by house, by form and by games. Boys lived and ate in twelve houses scattered around the town. They joined the school at, usually, thirteen or fourteen, and were graded academically by ability alone. A form might therefore contain boys of very different ages. The sequence of forms, as far as it concerns us, is laid out in Chapter 2. It is important to remember that, as is still general in Britain, the Sixth Form, and specifically the Upper Sixth, was the highest, corresponding in level to the American Twelfth Grade. Prefects (known officially as praepostors, unofficially as pollies) were drawn from the Upper Sixth, and boys left at eighteen if they had not left before. There were three terms in a year (Winter, Easter and Summer). The normal weekday timetable ran thus: school prayers, first school (that is, lessons), breakfast, second school, dinner, games, third school (except on half holidays), tea, private work, house prayers.

Games (fives, athletics, and above all football and cricket) were organised partly on a house and partly on a school basis. For each game, every house had its own two teams -- All Ages and Under Sixteen (or sometimes Under Fifteen) -- which competed for the inter-house challenge cups. School games of football and cricket were played on three grounds, the Lower, the Middle and the Upper. New boys would be placed in teams on the Lower or Middle and would progress, if they were good enough, to the Upper. The pinnacles of achievement were the Fifteen and the Eleven (graced with capital letters), which were the school's first teams at football and cricket respectively.

As we look back from the relatively liberated and egalitarian present (the emphasis being on relatively), we must allow for much social change. Yarborough has long been a pioneering and liberal school. It is so today, it was so fifty years ago in my own time, it was so -- markedly more than the Rugby of Tom Brown -- at the date of this story. But even the most pioneering and liberal public school of a hundred and twenty years ago preached what seems to us a very stern morality and tolerated what seems to us a great deal of injustice. Four historical facts should above all be borne in mind:

- Society was stratified by class and caste -- contempt for him who ventured above his station.

- School life was regulated by harsh discipline -- the cane for the rule-breaker and the slacker.

- Education was permeated by religion -- a foretaste of hell-fire for him who, in the Headmaster's eyes, transgressed.

- The gravest transgression of all was sexual activity between males -- the full stigma of the moral leper, unmitigated shame, upon him whose conscience surrendered to such lust. Lust it was invariably taken to be, for same-sex love lay beyond the comprehension of Victorian authority.

The original title was based, of course, on the adage that the child is father of the man. The new slant to the story suggests a new title, drawn from George Herbert's poem which is quoted in Chapter 31.

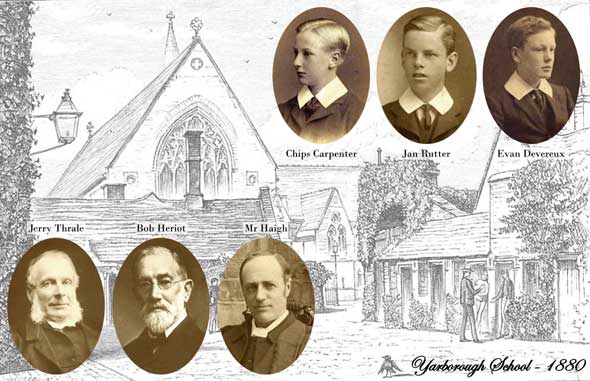

One final factor touches me personally: that the story's superstructure is built upon a tangibly solid foundation of reality. The school is so meticulously described that, although it remains anonymous throughout, it is instantly identifiable to anyone who knows Yarborough (which is but my own disguise for its real name). Many, maybe most, of Hornung's characters were likewise based on actual people, although he naturally changed their names. Bob Heriot and Jerry Thrale, so sympathetically portrayed, were real men and his real mentors. So too, the other side of the coin, was Haigh. Chips Carpenter, with his bronchial problems, his poor eyesight, and his passion for cricket, was Hornung himself, who in real life left Yarborough early because of his asthma.

Above all, some aspects of Jan Rutter, the hero of the tale, were borrowed from a boy who was a contemporary of Hornung's and in the same house; I could name him, but will not. In due course this boy's son also went to Yarborough, and ultimately he became a master there. He was still a master in my own day, and a most endearing and memorable one. It was only recently that I learnt of this connection; too late, sadly, to discuss it with him before he died. But, now that I do know, I count it a privilege to have sat at the feet of Jan's son.

I am grateful to Andy who has designed the frontispiece, and even more than usually indebted to those who have vetted drafts for style and comprehensibility: Chris with British, Neea and Ben with non-British eyes. And, as always, I have been wonderfully supported in every way by Hilary and by Jonathan.

Authors deserve your feedback. It's the only payment they get. If you go to the top of the page you will find the author's name. Click that and you can email the author easily.* Please take a few moments, if you liked the story, to say so.

[For those who use webmail, or whose regular email client opens when they want to use webmail instead: Please right click the author's name. A menu will open in which you can copy the email address (it goes directly to your clipboard without having the courtesy of mentioning that to you) to paste into your webmail system (Hotmail, Gmail, Yahoo etc). Each browser is subtly different, each Webmail system is different, or we'd give fuller instructions here. We trust you to know how to use your own system. Note: If the email address pastes or arrives with %40 in the middle, replace that weird set of characters with an @ sign.]

* Some browsers may require a right click instead