Gammer Gurton's Inglecock

Another indelicate frivolity

By Mihangel

Segment 4

There being nothing useful left at Bumley for Rob and me to do, we went home. I'd overrun my leave of absence and had to face the music. Showered with thanks, we took our leave of Charlotte and Alex and Hugo and William, and left the boys trying to train Piglet to obey orders. I spent the rest of the holidays working on the CD of the manuscript, typing it into a Word document, and comparing it with a facsimile of the 1575 quarto which I found on the web.

The new term brought the team together again. Rob and I, now prefects, found it not too difficult to keep our noses reasonably clean. The portrait of William, professionally restored and its frame regilded, was already adorning the library. Rehearsals started in earnest, and everything proceeded smoothly. Musicians and instruments were found. Rob and his assistants built the set, and the mobile house-front worked well. Much time was spent on positioning and lighting the Needle before the prologue, and on refining Cock's impalement scene. Hugo himself went down with the trots and Rob's tape recorder captured it with revolting fidelity. The timing of the sound effects was rehearsed again and again -- Hodge's trots, Gib's screech, Rat's fart, Diccon's belch on emerging from the pub.

Only one event from that period deserves fuller notice. Both Rob and I were applying for places at Christ's in Cambridge, I because Old Persimmon recommended it as especially strong in English literature, Rob because it was strong in science too and we simply had to stay together. Late in November the interviews fell due and we made our joint way there, in considerable trepidation because we knew the competition would be ultra-fierce. I was down to be interviewed by Professor Prufrock, a specialist in Elizabethan theatre whose name was well known to me. At the appointed hour, after an agonising wait, I knocked on his door and went in.

He looked up. His hair was white, his face florid and thickly bespectacled, his expression libidinous, and he seemed to be mentally undressing me. "Hmmm!" he said in a tone of approval. "Pray be seated! My name is Lancelot Prufrock, and this is my colleague Henry Plantaganet, who is a medieval historian by trade."

Plantaganet nodded to me, but he sat expressionlessly in the background and never once opened his mouth. Presumably he was there to see fair play, and had I been a historian their roles would have been reversed.

"Now," said Prufrock, opening a folder and peering at my application form. "Oh yes, of course. Samuel Furbelow from Hambledon. Reginald Persimmon is a good friend of mine, you know, and he keeps me informed about Hambledon productions. Let me see, you played Brutus in Julius Caesar, and Capulet in Romeo. Then you produced Edward II. That is impressive -- I trust it was properly explicit, and with a proper poker! Then you played Oberon in the Dream-- Reginald sent me pictures of that." He groped in the folder. "Yes, here is a fairy. It must be you. Very nice, very nice. And here is Puck." I could see, upside down, that it was a provocatively posed photo of Hugo in almost but not quite his full glory. Prufrock held it close to his glasses. "Remarkable, quite remarkable!Tell me, how was that fig-leaf attached?"

"Trade secret, I'm afraid, sir. But you could try asking him. He intends to apply here next year."

"Does he really? Does he really?"I could see the old man almost licking his lascivious lips. "What is his name?"

"Hugo Spencer." Prufrock made a note. "He's currently producing Gammer Gurton."

"Ah yes! And are you acting in it?"

"Yes. As Diccon."

"Imuch look forward to the event." So he was one of the scholars Old Persimmon had invited. "After all, we too have a proprietorial interest in Gammer. And Mr Persimmon tells me to come prepared for a surprise, but he refuses to be specific. I don't suppose," he went on almost pleadingly, relapsing into the vernacular, "you can spill the beans?"

"I'm afraid not, sir. I'm sworn to secrecy too." I had to play this carefully: to spill only enough beans to work to my advantage. "All I can say is that this performance will be the first complete one ever."

"Complete?You cannot mean you have a fuller text?"

"Yes, we have. In Stevenson's own hand."

"God in heaven!"He was blatantly gobsmacked. "How does it compare with the quarto?"

"There are plenty of minor variations that make little difference. But there are ten whole lines that were expurgated for the performance here, and for the quarto."

"And do they add significantly to the plot?"

"Quite a bit, yes. They're even, er, coarser than the rest. Good coarse undergraduate humour. Schoolboy humour, we'd call it."

"Undergraduate? Schoolboy? How do you make that out?" Prufrock sounded impatient. "Stevenson was a Fellow. Granted, he was not yet a Fellow at the time of his first play in 1550. But even then he was a graduate, and there is no evidence that that play was Gammer."

"But there is, sir. It was premiered, under the title Diccon of Bedlam,on 6th December 1550." He stared at me as a biologist might at a new species. Here, it was a positive asset to be geeky. "And even the quarto makes it clear it was written in 1549 at the latest, beforehe graduated."

He regarded me with his head on one side. "How so?"

"It hinges on the Latin mass, which few could understood. The prologue says of Dame Chat,

"Yet knew she no more of this matter, alas,

Than knoweth Tom our clerk what the priest saith at mass.

"Cambridge was very protestant. Christ's particularly so. On 7th March 1549 the Book of Common Prayer was published, the first in English. From 9th June it was compulsory to use it. After that, nobody here could possibly contemplate having a priest say the mass in Latin."

He goggled, mouth agape like a codfish. "Did Mr Persimmon put you up to that?" he said at last.

"No. I worked it out myself. It seems obvious, but as far as I can tell nobody else has noticed it."

He leant back and roared with laughter. "I nearly uttered," he confessed when he had recovered, "a naughtily insulting saying. But you are surely no babe, even if you are perchance a suckling. Yes indeed, it isobvious. Yet generations of professional scholars -- myself included -- have completely failed to notice it. When you join us here. . . I mean," he hurriedly corrected himself, "if we give you a place . . . you will be asked to write a first-year dissertation. Would you consider doing a critical edition of your new text? We would be more than happy to publish it."

"And I'd be more than happy to do it, sir." Best, I thought, not to say that I already had.

"Thank you." He reverted to undressing me in his mind. "And if Diccon is garbed in no more than tatters of clothing, I shall attend the performance in even greater anticipation."

Later I met up with Rob. His interview too had gone well. "I had an earnest young geezer called Mulligatawny," he reported, "who started talking about water gas. So I grabbed the opportunity and told him I'd had some experience of it. Lowe's process, it's called now. Squirt a jet of steam onto a coal fire and the reaction produces carbon dioxide and hydrogen. CO + H2O = CO2+ H2." (I hope I've got that right, because it's Greek to me.) "Nice and flammable -- that's why inglecocks work so well. Scrub out the CO2and you're left with pure hydrogen. There's a huge demand for that these days, and they're working on ways to cut down on the coal and the CO2. He said he's never met a student with such a grasp of the principles! I think I'm in!"

"I think I'm in too!"I told him about my lustful old geezer, at which he hooted with laughter. "Of course he was lustful," he said, hugging me, "if he was interviewing you."

Before we left we had a look at Christ's hall, where Gammerhad been produced all those years ago. A temporary stage knocked up at one end would be a different ball-game from our state-of-the-art theatre, but in its way more atmospheric.

*

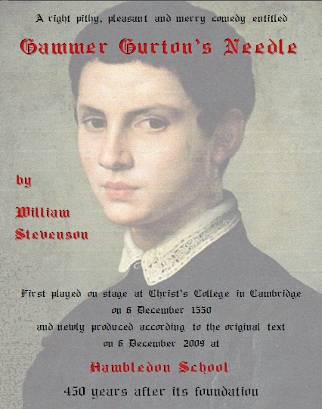

The performance drew near. A fortnight beforehand, a little exhibition was opened in the library. It consisted of only two cases. One contained a few unexpurgated sheets of the manuscript and a couple of sheets of music. The other contained the Needle and a diagram and explanation of what he did. Above the cases were the portrait itself and two wall panels, one about the Founder, the other about Gammer. Once word got round about how rampantly indecorous the Needle was, boys and staff came flocking to admire him.

The details of the programme were hammered out, and it was designed and printed. Hugo's notes were truly learned (and generous in acknowledging my help). He had agonised over the title -- should it be the original Dicconor the replacement Gammer? -- and plumped for Gammeras by far the better-known. At his own request, Alex's relationship to William was not spelled out. "I'd rather," he said modestly, "be down as just an ordinary actor. Which is all I am."

The details of the programme were hammered out, and it was designed and printed. Hugo's notes were truly learned (and generous in acknowledging my help). He had agonised over the title -- should it be the original Dicconor the replacement Gammer? -- and plumped for Gammeras by far the better-known. At his own request, Alex's relationship to William was not spelled out. "I'd rather," he said modestly, "be down as just an ordinary actor. Which is all I am."

Meanwhile, negotiations for the sale, in the tardy hands of valuers and solicitors, were grinding their slow way forward. By the end of November agreement was reached, and the school began to prepare a lavish brochure in readiness for an appeal to parents and Old Boys to raise the necessary million pounds. An artist and a sculptor were commissioned to create replicas of the portrait and the Needle once the celebrations were over.

Two days before the show, the Bumley Volvo delivered to Hambledon four hens and a Piglet markedly grown since our last encounter. They were given the hospitality of Twankey's garden shed, where Alex ministered to their needs. And they called for frenzied last-minute rehearsals. The hens were no problem. Rob had knocked up a wooden coop for them with a little run in front, far more rustic and Tudor than a modern metal one. They were positioned at the edge of the street, except in Act IV Scene 4 when they were taken indoors ready to be stolen by Hodge. And they behaved impeccably. Whenever Alex passed, they ran out in delight. Whenever Hugo passed, they scuttled inside. Whenever I clucked at them, they stared at me as if I was daft.

Piglet took longer to tame. To prevent him trespassing inside the houses, he was allowed only in the street and only when the drop was down, which meant just before or just after the prologue. To prevent him jumping off the edge of the stage, Rob installed a temporary electrified fence and, after some close encounters which made him squeal, Piglet learnt the lesson and the wire could be removed. He was released in the wings from the dog basket in which he had travelled, and he was supposed to scamper across the stage to Alex who was waving food on the other side. It took time, but he finally got the message. Perhaps animals were not so bad an idea after all -- though I would still draw the line at infants -- and even the dress rehearsal went without a hitch.

The great day arrived. In the afternoon, visiting scholars and critics traipsed into the library to view the exhibition, and some became a bit stroppy when Old Persimmon refused to let them see the rest of the manuscript until after the performance. A few of the cast were on duty as hosts, and I was there when Prufrock turned up. He greeted me warmly and made a beeline for the case.

"Phenomenal, quite phenomenal!"he exclaimed, poring short-sightedly over the manuscript. "And you have read this yourself? You can read Tudor handwriting?"

"More easily than I could."

"Precocious! Astonishingly precocious! And you still will not reveal what new text it contains?"

"You'll hear for yourself tonight, sir. But let me introduce Hugo Spencer, the producer."

"Ah yes! Ah yes!Remarkable, quite remarkable!"Prufrock declared, shaking hands and leering. And with reason, for Hugo was particularly vivacious and attractive today. "I hear, Mr Spencer, that you intend to apply to Christ's next year. You will be welcome, exceptionallywelcome." Hugo, doubtless spotting what lay behind this enthusiasm and more than capable of handling it, grinned as if his place was in the bag.

I called Rob over. "And may I introduce Rob Nethercleft who masterminded the set and the props?"

Prufrock shook his hand and gazed longingly. "Extraordinary!Hambledon engenders delights! But I am afraid I did not quite catch your name."

"Nethercleft, sir. Rob Nethercleft. Like Sam, I was interviewed at Christ's last month."

Prufrock smote himself on the forehead. "Mr Nethercleft! Dear me, I was at risk of forgetting! My colleague Dr Mulligatawny, on hearing that I would be at Hambledon today, asked me to convey the auspicious tidings that the college has accepted you, without condition. And to you, Mr Furbelow, I myself bear the identical news. This will of course be confirmed in writing. Meanwhile, my congratulations to you both. You will be outstanding adornments to the college."

Only when Prufrock turned to study the Needle could we worm ourselves away, take cover behind a bookstack, and hug hugely in relief.

Two hours later, the cast suffused with a warm feeling that all would go well, the show began. For fifteen minutes before kick-off, the curtain was up, the Needle was spouting its jet of steam, the fire was glowing steadily brighter, the actors were silently sewing, sweeping and pottering, the hens were pecking grain in their run. By half past seven the auditorium was full to bursting. A whole extra row of seats had been inserted to accommodate the learned visitors who, having been wined and dined by Old Persimmon and the headmaster, seemed in jovial mood. The drop came down. I ambled on-stage, a beggar's scanty tatters flapping loosely on my thighs and torso. A moment's pause to obtain silence, and I began.

"As Gammer Gurton, with many a wide stitch

Sat piecing and patching of Hodge her man's breech . . ."

The prologue finished, I ambled off, clucking at the hens as I went. Piglet was released and ran halfway across the stage before stopping and staring piggily at the audience. He had not seen so many people before, nor heard such a gale of laughter as they sent up. As he pondered them, he crapped copiously. Mercifully he then spotted Alex, and off he trotted. An excellent start, and such an eventuality had been foreseen. Tib came on with a shovel and mop, shrugged resignedly at the audience, and cleared away the mess. Up went the drop. As cries of lamentation issued from Gammer's house, I slunk out of the door, furtively tucking a joint of bacon into my rags. Diccon's part is a lovely one, not least because he serves as an intermediary with the audience.

"Many a mile have I walked," I told it conversationally,"divers and sundry ways,

And many a good man's house have I been at in my days . . ."

We were under way. The audience, forewarned by the programme notes, took the shower of shit and turds and arses and cocks in its stride, and soon was splitting its sides. All the introductory education paid dividends, for Cock's misadventure went down a bomb, and Hugo and Alex were on top of their form. The musical interludes were admirable. Everything was well.

At the end of Act III came the interval. The curtain stayed up, but I peeked at the audience through a crack in the house-fronts. The scholars and critics were crowded around Old Persimmon who seemed to be rejecting their congratulations. If so, very fair of him. Beyond commissioning the production, he had as usual had nothing to do with it. Then I spotted Charlotte in an earnest huddle with the headmaster and a well-groomed and tweedy couple I did not recognise. Hugo was peeking through the next crack, and I asked if he knew who they were.

"And how!They're my parents!" He was on a high, I could see, twanging with excitement. Understandably so. His labours were bearing triumphant fruit.

But it was time for Act IV. The musicians struck up, the audience reseated itself, and Doctor Rat waddled grumpily on.

A man were better twenty times be a bandog and bark,

Than here among such a sort be parish priest or clerk,

Where he shall never be at rest one pissing-while a day,

But he must trudge about the town, this way and that way . . .

And soon to the end. Gammer's needle was found, the loose ends were tied up, and the whole cast jostled into Chat's pub for a celebratory booze-up. But I lingered briefly for my epilogue.

But now, my good masters, since we must be gone,

And leave you behind us, here all alone,

Sinceat our last ending, thus merry we be,

For Gammer Gurton's needle's sake, let us have a plaudite!

As I followed them inside, the plauditeerupted, deafeningly and long. We ran on for our bows. Alex trotted off and returned with Piglet on a lead like a dog. The chickens had their applause. The musicians were hauled on-stage for theirs. Hugo got his thoroughly well-deserved ovation. And it was over. Unlike the last two productions, this one had gone entirely according to plan. We glowed with an almost orgasmic sense of achievement.

The rest of the cast trooped off to change, leaving Hugo, Alex, Rob and me to savour the triumph together in peace. But although backstage visitors were normally discouraged, this time an exception was made. We were invaded by a swarm of experts, accompanied by Old Persimmon and the headmaster. Most of them, full of praise and full of questions, homed in on Hugo. Prufrock, at the back of the queue, buttonholed me instead.

"The new material" he pronounced, "was indeed worth waiting for, and most ingeniously treated. I concur with your analysis that the humour is of an undergraduate or even a schoolboy nature. Hodge was masterly, and a sight for sore eyes. As also was Diccon." He was openly inspecting my tatters and whatever might be visible behind them. "But my eyesight is sadly not what it was. May I be permitted to contemplate your Cock at closer quarters?"

I blinkedfor a number of moments before the penny dropped. Alex had modestly stepped back, and when I beckoned him forward and introduced him, Prufrock looked him lecherously up and down -- especially down, at his skimpy torn jerkin and his bare legs.

"Astonishing!" he cried, "wholly astonishing!A most delectable Cock! So gushing with the joy of youth! Oh Hambledon, fons deliciarum! I trust that you too will consider adorning Christ's when the time is, ah, ripe."

Alex, not too innocent to read Prufrock's mind, seized on that last sentence as the only safe one. "Well, I hope so," he said. "There hasn't been a Stevenson at Christ's since William."

"A Stevenson? A Stevenson?"Prufrock was evidently not aware of Alex's ancestry, and one could almost hear the connections being made inside his randy old head. "I cannot believe it!"

"But it's true," I put in. "He's a direct descendant of William." I plucked Prufrock's programme from his hand and held William's portrait up beside Alex's face. The similarity was striking.

Prufrock peered from one to the other. "God's bones!"he boomed. "A Stevenson in the flesh! Ornament of Hambledon and would-be ornament of Christ's! Progeny of the school's father and progeny of the college's son! An uncommonly comely one to boot! We must act upon it! Yes!. . . Mr Spencer! Mr Spencer!"Unceremoniously elbowing an eminent critic out of the way, he grabbed Hugo by the jerkin. "In the summer, examinations over, you shall convey your cast to Cambridge. You shall stay at Christ's as our guests. You shall perform your Gammerin our hall. You shall parade your talent before our talent. Your charming Cock shall be the centre of attention, and we shall all come together. You shall not say nay!"

Dazed bythis barrage of insistence, trying hard not to laugh, we sensed a presence murmuring "Go on, go for it!". William, we abruptly realised, was with us, and had been with us all evening. He must have hitched a lift from Bumley in the Volvo.

So Hugo did not say nay. Nor did Old Persimmon and the headmaster. And at length the visitors were shooed away to the archive room to inspect the expurgations and assure themselves that we had not made it all up. Only Charlotte, who had been waiting quietly in the background, was left. She too was generous in her praise, but that was not why she had come backstage.

"News!" she said. "The appeal has been called off!"

We -- most of us -- stared at her aghast. "Oh God, why? Has the sale fallen through?"

"Quite the reverse. The money's already been raised. A single cheque, for a million pounds. Hugo, I don't know how much arm-twisting has been going on. But thank you."

I have never seen Hugo wear so beatific a smile.

Everyone else had gone home. While we removed our greasepaint and changed, Rob packed up the livestock, somnolent now after their exertions on stage, for their return journey to Bumley. We carried the basket and coop to the Volvo and loaded them in. By common consent, the five of us turned towards the library, which was next to the car park. The porter was locking up but, seeing like as how two of us were prefects and as long as we were quick, he let us in.

Rob and I were holding hands. So too were Hugo and Alex. Together in comradeship, we stood in front of the portrait. And I swear that William smiled at us. As for the little inglecock in his glass case, I swear that his pucker-mouth positively beamed.

Authors deserve your feedback. It's the only payment they get. If you go to the top of the page you will find the author's name. Click that and you can email the author easily.* Please take a few moments, if you liked the story, to say so.

[For those who use webmail, or whose regular email client opens when they want to use webmail instead: Please right click the author's name. A menu will open in which you can copy the email address (it goes directly to your clipboard without having the courtesy of mentioning that to you) to paste into your webmail system (Hotmail, Gmail, Yahoo etc). Each browser is subtly different, each Webmail system is different, or we'd give fuller instructions here. We trust you to know how to use your own system. Note: If the email address pastes or arrives with %40 in the middle, replace that weird set of characters with an @ sign.]

* Some browsers may require a right click instead