Sweet William

A fifth and final indelicate frivolity By Mihangel

Part 1

This tale, while rather more sober than usual, does contain some great impudences which I hope may be forgiven. My tongue, remember, is firmly in my cheek. The main characters are still the same, and the story will make much more sense if you have read the earlier frivolities beforehand. My thanks as always to Hilary, Pryderi, Alan, Anthony and Jonathan.

25 July 2011

"That sheep," I said. "I hope it can smile."

"Why?" Rob asked.

"If it's just been shagged by Alex, I'd expect it to be happy. Wouldn't you?"

The context of this conversation will not be obvious. Here's how it happened.

*

As Rob and I rattled along the branch line through the suburbs of Birmingham I began to relax. While my own family had dissolved into thin air, I had three proxy families to fall back on. Rob's and Alex's I knew and loved, but Hugo's was still something of an unknown quantity. Although his parents had already been incredibly generous to us, we had met them only briefly, and never before had we been to Pidley Hall, their home just outside Stratford-upon-Avon. Which was where, this June morning, we were now heading.

At the station we were welcomed by the three Spencers and by Alex who was staying with them. They whisked us down to the Royal Shakespeare Theatre where they had found last-minute tickets for the matinee of The Tempest, Shakespeare's final and most enigmatic play. But first we went for a snack lunch in the restaurant overlooking the calm waters of the River Avon and the sharp greenery of its weeping willows. While I would never, off my own bat, have burdened Everard and Hermione with my personal woes, they had heard the outline from Hugo, and with great delicacy they got me to spill more beans.

My parents had long bickered with each other and with me. They had ranted -- very loudly -- when I teamed up with Rob, they had ranted at my involvement with 'that acting lot,' they had ranted at my sordid -- their word -- productions and publications, they had ranted equally loudly at each other. Now they had reached the final stage. They were separating, selling up, and going their own ways; neither of which, they made clear, would accommodate me. No great sorrow at that, to be honest; rather a degree of relief. 'Home,' as one grows older, becomes an increasingly elastic concept. Yet most twenty-year-olds still hanker for some sort of base where some sort of welcome is on offer. Rob, that tower of strength, offered me the shelter of his own family as and when required, and so too did Alex and Hugo, all three with the enthusiastic backing of their parents. Now I had just transferred the last of my possessions to Rob's home, and we were following up Hugo's invitation to visit his own.

So far so good. The real and nagging problem, though, was that my parents would no longer fund me at Cambridge. With the coming hike in student fees, it was far from clear how I could make ends meet. Christ's might give me a hardship bursary. Or it might not. The thought of having to leave was hateful, and I said so. Everard and Hermione heard my tale with thoughtful sympathy. But the ten-minute bell rang.

"We'll talk more about this later, Sam," said Everard. "But now we'd better find our seats."

I won't say much about the performance, except that Sir Ian McKellen was Prospero and, of course, brilliant. We were in stitches over the camped-up innuendo in Act II when the drunken Stephano feeds his bottle into the nether mouth of the two-voiced monster. And that prompted Rob, as a relative newcomer to Shakespeare studies, to raise during the interval the long-standing question of whether the Bard had been gay.

"Bisexual, I'd say," was my reply. "Some of the sonnets addressed to the Fair Youth are fairly explicit. A few people argue that they're about platonic friendship, or that they're dramatic fiction, or even that our national poet couldn't possibly have been queer, could he? But personally I can't help reading them as autobiographical. Yet at the same time he had it off with women. After all, he got Anne Hathaway pregnant when he was a teenager and had to marry her in a hurry. Then there's the Dark Lady of the sonnets. And there's the lovely story that he overheard Richard Burbage -- who was one of the top actors of the day -- arranging to call on some lady that night masquerading as Richard III. But our Will got there first and was hard at it when Burbage arrived. 'Tough,' said Will. 'William the Conqueror came before Richard III'."

The play over, we returned to the restaurant for a cup of tea. There we debated the merits of the new Stratford stage -- the technical term is an apron or thrust stage -- which had been revamped during the recent alterations to project far out into the auditorium. The justification was that Shakespeare wrote for that sort of stage, with the audience on three sides, as in the reconstructed Globe in London. Which was true, up to a point. But at Stratford the apron is so long that, if the actors are at the front, much of the audience sees only the backs of their heads.

Rob was also shocked that the apron offered so little scope for scenery. Shakespeare, he allowed, intended playgoers to supply the setting from their own imagination. But audiences these days had to work hard enough to follow his language, which isn't easy. Why make them work even harder by starving them of visual clues? As a designer he firmly believed in the traditional proscenium-arch stage with its huge potential for tangible and credible settings. Authentic performances were all very well, he argued, for people who knew the plays inside out, but surely it was the duty of popular theatres like Stratford to make Shakespeare as accessible as possible, not to keep him obscure. Today's audience, to judge by its faces and accents, came from all over the world, and many of them were plainly puzzled by what was going on. He had a fair point.

We then did a quick tour of the main sights, for Rob had never been to Stratford. We looked at the half-timbered house in Henley Street where Shakespeare, the son of a glover, was born (in 1564, in case it has slipped your mind). We looked at the Guild Hall, the Grammar School in Church Street where he was educated, and Nash's House and Halls Croft where his descendants lived. All were heaving with tourists, as they always are in summer, and we went inside none of them. But we did go into the church to pay homage at Shakespeare's monument.

"Along with the Droeshout engraving in the First Folio," I explained to Rob, "this is the only certain portrait there is. It was done very soon after his death, when his friends and his widow were still alive, so it must be reasonably true to life. They must have given it their approval."

"But it's still not exactly prepossessing, is it?" Everard observed. "Someone said it makes him look like a self-satisfied pork-butcher. But maybe that's how he really did look."

Our little pilgrimage over, we drove out to Pidley Hall. It too proved to be Tudor and half-timbered, larger than Bumley Grange though by no means a full-blown mansion. True to the Spencers' socialist principles, the grounds and land were run -- very profitably, it appeared -- by a co-operative. Once a week in the season the house was opened to the public, unlike the nearby (and much grander) Charlecote Park which belonged to the National Trust and was open every day. Charlecote had been the home of Sir Thomas Lucy who, according to persistent tradition, had a series of run-ins with young Shakespeare over deer poaching; and he paid for it by being caricatured as Justice Shallow in The Merry Wives and Henry IV Part 2.

Pidley, like its owners, was warm and friendly, and over a very good dinner Everard told us something about the history of the Spencer family. Stick-in-the-mud, he surprisingly called it, and indeed (until very recent times) conservative. For generations all the Spencer menfolk had gone to Hambledon and Christ's. For generations the name of the eldest son had alternated between Everard and Hugo -- changed by the Tudors to Hugh, by the Victorians back to Hugo. For generations -- as far back as portraits survived -- all Spencers had had flaxen, almost golden, hair. For generations the family had kept its head down. Ever since 1326 when an early Hugo Despenser ("Young Spencer -- you know all about him") was put to death in a particularly revolting manner for supporting Edward II, his descendants had kept out of the political limelight and lived the quiet life of local squires, not even playing any part in the affairs of Stratford.

After dinner Everard gave us a guided tour. One interesting port of call was the gallery, a long narrow room lined with portraits of blond squires -- all remarkably similar in face -- and their ladies. "But no earlier," he said, "than the seventeenth century, because the gallery was burned out in 1627. We've only one older painting. We found it stashed away in a storeroom, and we've no idea who it is or how it got here." He pointed to a small roundel on paper, a foot in diameter, which depicted a rather charming boy with dark auburn curls. "The pundits say it's Italian work, about 1580."

"I'd like to think," said Alex unexpectedly, "that it's Shakespeare . . . He looks," he added, "rather like me." Indeed, hair colour apart, he did, remarkably so.

"So would I," said Everard. "But it's wishful thinking. In 1580 he was sixteen and a nobody. There's nothing whatever to link him to Pidley. And why should he be painted by an Italian? Much more likely some eighteenth-century Spencer brought this back from a Grand Tour."

Much more likely. None the less the Cobbe portrait -- one of the few with a reasonable claim to depict the Bard -- has dark auburn hair. So too, though a less plausible candidate, does the Sanders portrait. And it is on record that the memorial bust in the church originally had auburn hair before it was repainted. But none of that was evidence of anything.

From there to the library, the walls lined high with bookcases and the air heavy with the inimitable smell of old leather. This was territory I loved, and I cried out in delight. But the others claimed weariness and peeled off to bed. "Knowing you, Sam," said Rob, "you'll be here till all hours. Don't worry about me," he added generously. "Don't come up till you're ready."

"I'll be up in a minute too, dear," Everard called to Hermione. "I'll just get Sam introduced and then leave him to it. Mercifully," he went on to me, "the library was spared the fire, so we've got a few incunabula and quite a lot of Elizabethan stuff."

"Was the current Spencer a bibliophile, then?"

"It looks like it. It was an Everard, who seems to have been interested in history and topography. He died in . . . I never can remember dates, but here's the family tree . . . let's see, that Everard died in 1591. I'll leave this out in case you need it. And the catalogue's on the computer -- you'll find a shortcut on the desktop. Oh yes, and this'll interest you. We've a number of Shakespeare quartos too -- on this shelf here. When you've finished, would you lock up and set the alarm?" He showed me how. "Goodnight then, Sam. Sleep well, when you get round to it. We'll pick up our chat about your future tomorrow, but no hurry to get up in the morning." And off he went.

Left to myself, I browsed through the quartos. A word is needed here about the publication of Shakespeare's works. The definitive collection is the First Folio produced in 1623, seven years after his death. It contains the canon of his thirty-six plays, of which exactly half had not been published before. Had it not been for this labour of love by his friends, these eighteen plays, including Macbeth, Twelfth Night and The Tempest, would have been lost for ever. But the other eighteen had already been published in Shakespeare's lifetime, in slim individual quartos most of which were carelessly edited and crudely printed. Many survive in only a small handful of copies. Probably all of them, in those days before copyright, were done without his consent. In contrast, his four volumes of poems are meticulously printed, evidently under his supervision.

For a private library the Pidley quartos formed an almost incredible collection. They numbered fifteen, bound not quite identically but similarly, as if by the same binder but at different dates. Plays, in Tudor times, were down-market publications, almost an equivalent of cheap paperbacks today. They were normally sold unbound at sixpence apiece, and it was up to the customer to have them bound should he wish. All but two of the Pidley quartos were Shakespeare plays, the others being his poems Venus and Adonis and The Rape of Lucrece.

Then something odd struck me. All fifteen were published between 1593 and 1600. I went to the computer and checked with Wikipedia. Yes. Represented here was every single work of Shakespeare that appeared down to 1600, and not one that appeared thereafter. Were there later ones on another shelf? No. The catalogue confirmed the total really was fifteen. Its entries were listed by date of publication. Before the quartos came a whole string of books, many of them first editions of enormous interest and value but of no present concern to me, which included such historical and topographical gems as Camden's Britannia, Leland's Assertion, Stow's Annals, Holinshed's Chronicles, a Sebastian Munster, Joscelyn's De Excidio, an Olaus Magnus. This series ended in 1591 and was clearly acquired by the bibliophile Everard who died in that year. Then came the quartos. But after 1600 there were no entries at all -- evidently the current Spencer was not interested in books -- until the 1640s, when such godly authors as Sir Thomas Browne, Jeremy Taylor, Bunyan and Milton began to appear.

I checked the family tree. On his death in 1591 Everard the bibliophile was succeeded by his son Hugh, who was born in 1560, married in 1587, and died quite young in 1601. With his death the influx of quartos abruptly stopped. During his ten years as squire of Pidley, therefore, Hugh added fifteen books to the library, and every single one was a Shakespeare. The conclusion had to be that he was a Shakespeare fan, and that he had bought them himself. They were hardly gifts from the author -- who would give away shoddy pirated copies of his own work? -- and none of them had any handwritten dedication. But that reminded me of an entry in the catalogue, embedded in the middle of the earlier historical and topographical collection, which I had noticed the first time round but had not bothered with.

I looked it up again. Geneva Bible, London 1578, with manuscript verse to H.S. from W.S. 1579. I was instantly on full alert. Among all those priceless rarities, this book was an odd man out. The Geneva Bible, first published in full in 1560, was a mould-breaker -- far more so, to be honest, than the King James Version. It was the first bible in English to divide the text into numbered verses and, much more important, the first to be mass-produced and sold at a price of less than a labourer's weekly wage. It went through hundreds of editions. It is not therefore a rare book, even today.

As a bible, then, it seemed to hold little of interest. But the verse . . . In my present state of mind there was promise in anything to do with H.S., and special promise in anything to do with W.S. The book, when I located it on the shelf, proved to be squat and thick, about 8½ inches high, and inside the front cover, in careful handwriting, were the words:

H.S.

This holie booke perused,

Each iote and tittle scand,

The truth heerein diffused

Plaine shall you understand.

W.S.

August 1579

Hmmm. Was that promise empty after all? It was likely enough that H.S. was Hugh Spencer, who in 1579 was aged nineteen. But it was also likely enough that W.S. was merely a relative presenting him with a bible as he entered manhood. I consulted the family tree, which was very detailed. No, that wasn't the answer. At the right period there was no W. Spencer at all. Well, the initials were hardly rare -- there must have been thousands of W.S.s sculling around England at the time. True, one of those thousands was William Shakespeare. But why should the fifteen-year-old son of a humble glover give a bible to the son of the squire? I looked again at the handwriting. It was in secretary hand, the usual script of the day, without much character, neatly done in formal copy-book style as if by a schoolboy carefully remembering his writing lessons. Interesting, but proof of nothing.

Old bibles like this often contain handwritten notes. The blank endpapers and the blank sheets facing the title pages of the Old Testament, Apocrypha, New Testament and metrical psalms were a standing invitation to insert pious texts or records of family births and deaths. I inspected them, but all were empty. The book seemed hardly used, and apart from some foxing -- those brown patches caused by mildew -- it was in excellent condition. But yet, but yet . . . By the pricking of my thumbs, I misquoted to myself, something cryptic this way comes.

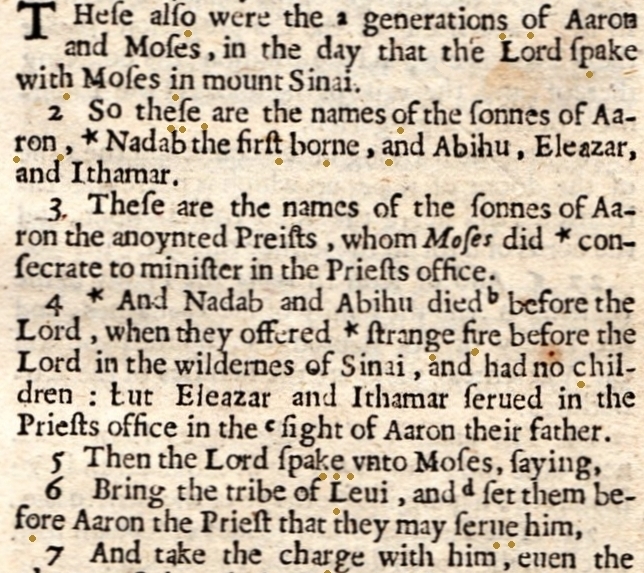

That verse niggled at me. This holy book perused, each jot and tittle scanned, the truth herein diffused plain shall you understand. Taken at face value, it was unremarkable. Yet did it hold a hint of something out of the ordinary? Was I astray in smelling a riddle in it, a coded instruction? Each jot and tittle. Was that a clue? Jots and tittles meant tiny little things -- serifs on letters, dots over i and j. The phrase came somewhere in the Gospels, didn't it? Google quickly located it at Matthew 5:18, and I looked it up in the Geneva Bible. Till heaven and earth perish, one iote, or one title of the Law shall not escape. Still not promising, and that page was as empty of annotations as the rest. I turned back at random, large chunks at a time, through the Apocrypha, through the minor prophets, through the major prophets, through the poetic books, through the histories, into the Pentateuch, and every page I looked at was clean. Until . . .

I nearly fell out of my chair. I had landed in chapter 3 of Numbers, and that page had been tampered with. I had to look hard to see it, but under various letters, even under spaces between words, were faint dots of sepia-coloured ink. Were these the jots and tittles?

Grabbing pencil and paper, I feverishly copied the dotted letters in sequence. As I read the result through, I felt the hair crawling on my neck. Not only did it make sense, but it was in blank verse: . . . osophies or tragicke louers foyled of their intent by unrespited grudge of destinie.

I flipped forward. The dots continued to near the end of Deuteronomy and there stopped. Holding my breath, I turned back to the start of Genesis. That, of course, was where I should have begun, because that was where everything began -- In the beginning God created the heauen and the earth. And there too began the dots. Mechanically I wrote the letters down . . . and found myself staring at a title, the author, and the opening of the text.

swete william a plaie by will shakspere churche strete lucy soon shall we haue him pinioned in the stockes

No capitals, no punctuation, no line breaks, typical unregulated Tudor spelling, but, as far as my numbed brain was capable of absorbing it, clear enough. I desperately wanted to carry on, but found that I could not. Not by myself. I had to share my discovery with everyone. And reaction was setting in . . . throat dry, heart palpitating, mind and belly churning.

Stagger upstairs. Into our room, shake Rob viciously, bleat "Library! Now!" Hammer on Hugo and Alex's door, open it to croak the same message. Feel a surge rising unstoppable in my gullet. Dive into a nearby bathroom, crouch over the great white telephone to God, heave out my soul. Find Rob beside me, his arm over my shoulder, offering a glass of water to wash my mouth. Turn round to sit on the floor, leaning back against the loo. The world fell slowly into place. Hugo and Alex, in a barely decent state of undress, were kneeling in front of me. Everard and Hermione, dressing-gowned, hair on end, were hovering anxiously in the doorway. They must have been roused by the din.

"He said something about the library," Rob replied to their raised eyebrows.

"Fire?" asked Everard in alarm.

"No," I managed. "Shakespeare. A new play."

And, tight in Rob's arms, I dissolved into tears. Faintly I heard gasps and a clamour of disbelief. "If Sam says he's found a new Shakespeare play," declared Rob stoutly, "then he has. But we're not going to look at it till he's ready."

At this point I must annoyingly interrupt the narrative with a word of excuse for my weaknesses. Undiscovered plays by Shakespeare simply do not exist. Scholars have traced his contribution to a few collaborative ventures such as Sir Thomas More. He wrote Love's Labour's Won and had a hand in Cardenio, but both are lost and the most determined efforts have failed to unearth either. Not a single new Shakespeare play has emerged since the publication of the First Folio in 1623. The starry-eyed may dream of finding one, but they never do.

Until, that is, now. For over four hundred years the thing had been sitting in full view on a shelf in the library of Pidley Hall, within two miles of Stratford, waiting for some geek to stumble across the key to its simple code. And that geek had turned out, by chance, to be Sam Furbelow. A very good reason, I felt, to sob my heart out with no sense of shame whatever. And another good reason was the contrast between the sterile chill of my dismembered home and the unstinted warmth of Pidley -- not just Rob's ever-present love, but the deep fellowship of Alex and the Spencers. Every one of them understood the chaos in my mind, both strands of it, and every one of them supported me.

"Quite right too," I heard Hermione say. "But I'm going to make some coffee. I'll bring it upstairs."

"No," I managed again. "Library. Give me five minutes and I'll be all right."

And after five minutes I was all right, more or less. The boys, having flung on more clothes, solicitously shepherded me downstairs. Hermione brought in a tray of coffee and biscuits. Caffeine began to restore me to a more even keel. I explained how the dates of the quartos, suddenly stopping at the time when Hugh Spencer died, suggested that he had been a Shakespeare fan. I showed them the verse in the bible, which everyone pored over -- but only after I had forbidden them to bring coffee cups anywhere near. It had been given, I pointed out, to an H.S. who was very probably Hugh Spencer by a W.S. who could just conceivably have been William Shakespeare. I explained how the jots and tittles worked. I showed them my transcription of the first page, which proved that W.S. was not just conceivably William Shakespeare, but really was William Shakespeare:

swete william a plaie by will shakspere churche strete lucy soon shall we haue him pinioned in the stockes

There were yells of incredulous delight. Hugo and Alex bumped fists. Everard and Hermione danced a little jig. Rob simply squeezed me.

I did a quick scribble. "Put it into modern form," I said, "and it looks like this."

Sweet William

A play by Will Shakespeare

Scene Church Street.

Lucy: Soon shall we have him pinioned in the stocks.

"Sam, oh Sam!" cried Everard, embracing me. "You marvel! You miracle! You genius!"

"That's as far as I've got," I said apologetically. "It's going to be quite a job to transcribe it. And it must have been a monumental job to dot it in. No wonder he didn't bother with capitals or punctuation or line breaks, and kept stage directions to a minimum."

"A bare minimum," Everard agreed, looking again. "Church Street? Stratford?"

"Probably. No doubt we'll find out."

"And Lucy's obviously the first character to speak. Sir Thomas Lucy, do you suppose, young Will's arch-enemy?"

"Likely enough. We'll see."

"So it's a juvenile work."

"Yes. The best part of ten years before his next. We mustn't expect a Hamlet."

"How do we tackle it, then? You're in charge."

"Are you happy," I asked generally, "to keep at it all night?"

Needless to say, they were. "Happy to keep at it all tomorrow if we have to," said Everard. "Well, all today, given the time." It was almost one o'clock. "When my secretary turns up I'll get her to cancel my appointments. Everything else takes second place."

So I organised three teams, one on the library computer, the others on laptops we brought down. Hugo dictated the dotted letters and spaces to Alex who typed them in. At intervals Alex put the resulting chunks of raw unedited text onto a stick which he passed to Hermione and Everard, who got it into lines and added capitals and punctuation as appropriate. Their results came in turn to Rob and me, who further edited it with expanded stage directions and added numbers to scenes and, tentatively, to acts. It took time to get into the rhythm. If Hugo was dubious whether a mark was an intentional dot or an accidental spot of foxing, a question mark had to be inserted. Sometimes he lost his place, and took a while to recover it.

But we ploughed steadily ahead. It rapidly became clear that Will himself was a central character, and that Hugh Spencer was another. It also became clear that some of the subject matter was quite uninhibited. In his maturity, Shakespeare was happy to employ sexual, even gay, innuendo. Here, in his youth, he went beyond innuendo, though nothing like as far or as crudely as Rochester did later in Sodom.

Our quiet mutterings might be interrupted by an "Oh my God!" or a snigger or even an outright bellow of laughter. There came a point when Hermione positively screamed. She and Everard were the first on the production line with a real chance of reading the text as sentences rather than as strings of letters. "His portrait was painted!" she shrieked. "By an Italian! On a roundel!"

We abandoned our tasks and crowded round her screen. "Yes!" cried Everard. "In left profile! And he had sorrel hair! Meaning dark auburn! Alex, you were right after all! Oh, brilliant!"

He cantered off to the gallery. Hermione seized the chance to renew the supply of coffee, and some of us seized the chance for a pee. Everard came back with the portrait which he propped in front of us. It was good to have Will -- a now-authenticated Will -- overseeing our labours, and we somehow felt that he was chuffed to see his own labours unveiled at last, more than four centuries on.

"How far through are we?" I asked Hugo.

He compared the thickness of the pages already done with those left before the end of Deuteronomy. "Half way," he said. "Or a bit more." It was now after five. "But I'm going cross-eyed with these damned dots. Alex, dear Alex, can we swap over?"

Back to the grindstone. Soon afterwards Hugo spluttered. Perhaps he was better than Alex at reading the raw text he was handling. "Oh, dirty!" he declared. "If I've got it right."

"Filthy!" Everard agreed when it reached him.

"But very funny!" Rob cackled when it reached us.

Before long it became clear why Will had chosen so laborious a method of perpetuating his work. The play had been written not for the stage but for Hugh and himself alone, as a private memento of their fun and games. And Hugh, fearful that his parents might discover his copy, had insisted that it be disguised. The current Spencer parents, thank goodness, were infinitely less prudish.

Finally, at half past eight, with another bellow of laughter, we reached the end. Knackered but fulfilled, we sat back and looked at each other. "I don't for a moment think it's a fake," I said. "How could it have been planted? But it needs to be authenticated scientifically, the sooner the better. And right now," I ventured to Hermione, "might I suggest a bite of breakfast? Meanwhile I'll print off six copies so we can read it end to end while we're eating."

"I second that," Everard said. "But give it me on a stick and I'll print three copies in the office while you do the other three here. My secretary'll be here any minute, and I've got to square her. And I think I'd better put Will and the bible into the safe, don't you? They're worth umpteen million pounds more than they were a few hours ago."

And so it came to pass. Hugo and Alex went off to help Hermione with breakfast, Everard went off to organise security and secretary, and Rob and I collated the printed copies. Before long, over our bacon and eggs and toast and marmalade, we were reading Sweet William properly for the first time.

By now the impatient reader will be feeling left out and wondering what the heck this damn play is about. So here it is in full, modernised in spelling and with punctuation added. I have also inserted the list of characters and relatively generous stage directions. Will had given no more than the briefest of pointers to who was who and what happened where. Apart from the labour of dotting it all in, this was no doubt because the play was for his and Hugh's eyes alone. It was a more or less factual account of their own deeds. They already knew the background and for that reason did not need detailed directions. But modern readers do. My additions, therefore, are what I have deduced from clues in the text.

The following -- if I may indulge in a little advertising -- is essentially the same as you'll find in Sam Furbelow (ed.), Sweet William: an acting edition (Cambridge University Press, 2013), 74pp., paperback £7. Should you want a long introduction and copious and (I hope) scholarly annotations, may I modestly refer you to Sam Furbelow (ed.), Sweet William: a critical edition (Cambridge University Press, 2013), xvi + 312pp., cloth bound £50, paperback £25?

Authors deserve your feedback. It's the only payment they get. If you go to the top of the page you will find the author's name. Click that and you can email the author easily.* Please take a few moments, if you liked the story, to say so.

[For those who use webmail, or whose regular email client opens when they want to use webmail instead: Please right click the author's name. A menu will open in which you can copy the email address (it goes directly to your clipboard without having the courtesy of mentioning that to you) to paste into your webmail system (Hotmail, Gmail, Yahoo etc). Each browser is subtly different, each Webmail system is different, or we'd give fuller instructions here. We trust you to know how to use your own system. Note: If the email address pastes or arrives with %40 in the middle, replace that weird set of characters with an @ sign.]

* Some browsers may require a right click instead