Enough Rope

by Joe Casey

Chapter 11

Now

One day, shortly after Ellen passed, my daughter Sarah insisted that I get some kind of social media account, something that I had, so far, steadfastly resisted. It had never seemed particularly important for me to have one; it was somewhat dangerous for an academic to have such an account, anyway. Everything I had to say to someone could be said to them either directly or, at a minimum, through electronic mail. The university had its own setup for facilitating communication between teachers and students, and that was good enough for me.

"You need one," she told me.

"Why?"

"So we can keep in touch."

"You live less than two miles from me."

"You're being stubborn."

"No," I responded. "I'm being intransigent. There's a difference."

"What if something happens?"

"Like what? I pitch face forward into my soup, one day?"

"Not funny."

"A little funny," I countered.

I let myself get coaxed into it, if only to keep her happy. I watched as she clicked and moused on the on-its-last-legs laptop the university had issued me several years ago.

"You need a new computer, Dad."

"Aaand here we go …" I pulled a face. "I'm not sure you understand the meaning of that word. Need. "

"I'm serious. This thing is so slow …"

"It's fine, Sarah."

"I'll see if Matthew can recommend anything. They aren't that expensive, any more."

"Sarah, don't bother your brother with this. He's always trying to get me to …" I trailed off as I watched as she worked. "How did you get so good at this?"

"Well, it's my job. Plus, I have to keep one step ahead of the kids. Knowledge is power, right?" She turned the computer to face me, showed me what she had done. "Anything you want to add?"

"I don't know. Looks like you've got everything. Maybe too much? What else do you want? Height? Weight? Shoe size? Inseam? Turn-ons? Turn-offs?"

She chuckled. "This isn't Tinder, Dad."

"Too bad. Might be more fun."

"Well … what about a profile picture?"

"There's something on my university account, I think."

"Yeah, one that was taken thirty years ago, when you still had hair. Anything more current? Say, from this millennium?"

I pointed at the screen, at the default place-saver image. "What's wrong with the white silhouette on the light blue background?"

"Well, if that's what you want …"

In the end, I let her take a series of pictures of me with her phone, picked the image least likely to frighten people, watched as she uploaded it to my computer and made it into a profile picture.

"Is that really how I look?"

"Why, what's wrong with it?" she asked. "You look fine."

"I look like an old man."

"Hate to break it to you, Dad, but you are an old man."

When Sarah got home, she sent me some test messages to make sure everything was set up correctly. Trying to play along, I sent back a few of my own … but after that initial meager burst of activity, I seldom thought about the page.

Slowly, though, evidence of my scintillating debut upon the social media scene filtered through the rest of the internet, and friend requests starting showing up. At first, it was family, for the most part: children and grand-children and I allowed them into my little virtual realm, figuring that they would, above all, simply be as bored by me here as much as they seemed to be in real life and would soon lose interest. Then, more distant relations knocked on the door, aunts and uncles and cousins twice and thrice removed. Those I largely ignored.

People from work, next, other professors, some graduate students … all of whom were, as far as I was concerned, strictly on a probationary status, likely to be hidden at a moment's notice. There weren't too many of those; I saw most of these people on a weekly basis and didn't care to know what they had eaten the night before or what kind of mood they happened to be in at any particular moment.

But, then, another bit of my past crept in: people from my youth, from St. Louis.

Most of these, I dismissed out of hand; there had been nothing particularly memorable about my time there - beyond the intimate drama of our family, centered mostly around Tom - and I had no desire at all to rekindle friendships and acquaintances that had never really been there in the first place.

Until one in particular showed up.

I sat there, looking at the one image, that of a man of a certain age - my age - and it struck me again how true was that trite saying; time was, indeed, a great leveler. Everything fell victim to the predations of time, beauty above all … and this man had once been beautiful, astonishingly so. I could see, in the timeworn but still handsome face presented to me, traces of the boy that had been, the set of his eyes, his mouth, the shape of his face.

Of course, it was Paul Warnock.

The temptation to ignore his request was there, of course, and probably the safer choice, as well. It took only his name to conjure up the memory of the last time I had seen him, in my bedroom, listening to him talking about my brother, trying to shock me with the graphic intimacy of their relationship.

Everything that had happened between us was, on the face of it, ancient history; it would have been foolish of me to think that a schoolyard friendship - even one fraught with this kind of strangeness - would have had any chance of surviving to the present. I had had a life after high school, one whose course I could never have predicted at the age of fifteen, and I assumed that Paul had had a kind of life, as well; perhaps for him, too, this was nothing more than ancient history, best forgotten for the childishness it was.

I moused over to the image and the choices presented beneath it, felt like the character in that hoary short story trotted out to high school freshman English classes everywhere. The lady or the tiger? I muttered to myself, before I chose the tiger.

As much as I hated to admit it - and would never admit it to Sarah - I enjoyed talking, even through this medium, to Paul. An initial awkwardness between us had yielded slowly to a tentative sort of friendship. We each uploaded pictures of our pasts for each other to study: I of my life here in Evanston, pictures of Ellen, of my children and grandchildren; he of a cozy little Depression-era brick Tudor in Atlanta, tastefully furnished, a small and well-kept garden in the back. No significant others in any of what he sent.

I had expected nothing more than this and was happy enough with it, so the next stage of it took me by surprise.

Did you get your invitation? he sent, one day, by way of the message application built into the software.

Invitation?

To our fiftieth?

Sorry to be so obtuse … fiftieth what? I responded.

High school reunion, of course.

Uh-oh. I'm not sure. Maybe?

Well, I've got mine. I was wondering if you were going. Chum in the water, I thought. Look out for sharks.

I had, of course, thrown out the invitation as soon as I had received it, as I had done with every other one that had been sent me throughout the years, dismissing as some strange kind of perversion the need to revisit a place and a time that was, for many people - well, for me at least - the source of a great deal of bother, something to be endured, gotten through, escaped, forgotten.

I think I may have tossed it out , I told him, hoping that that might put an end to the discussion.

Oh. Well, I think there's still time. I can e-mail a copy of mine to you.

Where is it to be held? Equivocating, one of my few talents. It had driven Ellen crazy every time I did it.

SLAM , he wrote back. The St. Louis Art Museum, in Forest Park … not all that far from the school. Another bit of memory poked its head out of the gray sludge of my brain: Tom, after Paul had left, had admitted to hanging around the museum near closing hours, hoping to pick up men. More chance of them being queer, he'd said to me. Safer than going into the woods. They tend to take you back to their apartments. And the pay is better.

I hesitated; Paul noticed it. You don't have to go, Tim. I understand. But I hope you do.

What harm could come of it? I wondered. Go, spend a few hours in his company, leave if you don't like it or feel uncomfortable.

Okay, I wrote back. Thanks.

"Who's Paul Warnock?" Sarah asked me, one day, over to borrow some of my research material for a project she was putting together for her class.

"Oh, just a friend from high school."

"That's nice. I'm glad to see you're making friends. Even if they're just online."

"I'm so glad you approve." Trying to keep the edge out of my voice. "Do you need to meet them before we can hang out together?"

"That's not what I meant," she chided. "I'm just … well, I just don't want to see you get lonely."

"I'm not lonely, Sarah."

"You're rattling around this house all by yourself."

"I enjoy rattling. It scares off the ghosts. Anyway, I get all the socialization I can stand at the university."

"Daddy …"

"Sarah …" So much of Ellen in her. Both the good and the bad bits.

"You don't need to be so defensive."

"I'm not being defensive. All of this was your idea, I might remind you. I never promised to keep up with it."

She said nothing; I could almost hear her counting to ten. "Fine. Cancel your account, if you want. I don't care either way."

Ah, but you do, I thought. This is how it started, I knew. First this, then unannounced "I was just in the neighborhood" visits, then "maybe you need to quit driving," and then being spoon-fed lime jello or oatmeal while wearing a bib. I made a mental note to pick up some cyanide pills at the drug store.

"Paul was my best friend, actually. Back then."

"Oh? Well, it's nice that the two of you reconnected."

You don't know the half of it, I thought. And then I thought maybe she did need to know the half of it.

"He knew Tom, as well. Did I ever tell you about Tom?"

"Your brother? Only that he died in Vietnam, back in the seventies. Why?"

"Well … there's a little more to that story." I looked steadily at her; she frowned. "Paul and Tom used to be an item, back then. In high school." There, I thought.

It took her a moment to understand. I waited. Each new generation thought that it understood fully the lives of those of the previous ones, fitted them into neat little recesses, robbed them of any sense of excitement or novelty. I supposed that I did the same with my parents, and they with theirs. Each generation thought that it was the first one to discover things that have been going on for hundreds of generations. What Paul and Tom were to each other was not new, had never been new. Nihil sub sole novum.

"Are … are you serious? "

"Never more so," I answered.

"How did that happen?"

"How does it ever happen? It just does."

"What did Nana and Papa do?"

"Nothing. They didn't know. Until much later, that is. After Tom died."

"But Tom told you . Right?"

I nodded. "Near the end. Right before he volunteered to go into the Army. Your uncle and I weren't the closest of brothers. He always had this … anger about him, and none of us ever understood why. He always seemed to take it out on me, and one day I got tired of him beating the shit out of me for no reason and I made him tell me what the fuck was going on."

I seldom swore in front of my children; I always thought it unbecoming for a parent to resort to that kind of language. Perhaps it was more of my reaction to my mother, to whom swearing had been part and parcel of who and what she was. Perhaps I simply wanted to shock Sarah out of her complacency.

"And that was the reason?"

"It was. He knew that that was what he was and he was afraid of it."

"Why are you telling me this?"

I looked at her for a long moment. "I need you to understand that even though I have been your father for forty years I am more than that. All of us are. We are ourselves and have our own lives. I got tired of people telling me I had to be this or do that, for no reason, and I decided one day - after Tom died - that I would live my life on my own terms and for my own reasons." I took a breath, watched Sarah open her mouth to speak, barreled over her. "I love you and I love your brother. That will never change. If and when I need your help with something, I guarantee that I will ask you for it. Until then, you need to let me live as I please."

Sarah pinched the bridge of her nose with her thumb and middle finger, her tell - ever since she was little - that she was about to cry. I had not meant to make her cry.

"Daddy, I'm … I'm sorry. I just … well, I'm just trying to do what I think I'm supposed to do." She blew out a harsh breath, all nerves. "You're getting older and I don't know what to do about it."

I relented. "I know, and I love you for it. I know that it's not easy. It never is." Thinking of, firstly, watching my father die, and then my mother.

She turned to look out the window into the emerald green of the back yard. We could hear the drone of mowers in the distance.

"Would I have liked him? Tom?"

I thought about it. "I … don't know, Sarah. Maybe. In time, if he had ever been able to come to peace with what he was. I'm not sure I ever liked him, not back then. We were very different people."

She turned to me, smiled. "Tell me about him?"

And I did.

The thing was - despite what I had told Sarah - that I was lonely. Not overwhelmingly so, but it was there, deep down in the savanna-dwelling primate part of my brain, the part that wanted nothing to do with books, and poetry, and music, and teaching, the part that wanted simple, basic contact with other people.

All of the higher-brain stuff helped, of course, to stave off the worst of it; they were all ways to experience other people, if only tangentially. Teaching, too, brought its own rewards … but I knew that my teaching days were numbered, that very soon I would have to listen to my younger colleagues gently suggesting that perhaps I might be happier if I stepped away from the game, accepted an emeritus position, and spent my days puttering around the garden.

And I hated gardening.

I had two years with Ellen between the time of her diagnosis and the time of her passing, and while I could never say that those were the two best years of my life, there was something in them that I thought was a rarity. The pain of her suffering came and went; on the best days she was very nearly as she always was, but as she progressed, those days came farther and farther apart. On the worst days, I would crawl into bed with her and simply spoon next to her, letting my body adapt itself to her, letting the contact say all that we needed to say to each other, willing my vitality into her. There was nothing sexual about it - those days were gone - but it managed to transcend the particularly selfish nature of sex and allowed me to be there for her as she negotiated the nature of her death.

But, now? What did men of my age do at this point in our lives? The more foolish of us, I knew, still chased would-be partners, still relished the purely physical abstractions of love. The rest of us, perhaps more introspective and less held in thrall to sex, would probably have been happy simply to have someone to go get a coffee with.

I went to my computer, called up Paul's profile, spent an uncomfortable amount of time studying his profile as memory and desire whispered to me from a time long gone.

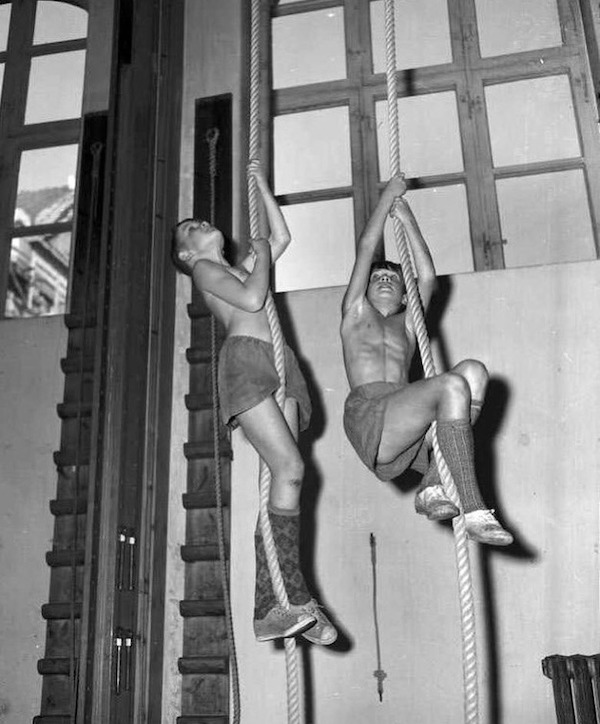

This 14 chapter story was created for the Inspired by a Picture: The Only Way is Up! Writing Challenge. The picture that inspired the story is:

Gymnastics at Ila school By Leif Ørnelund / Oslo Museum, License: Attrbution-ShareAlike CC BY-SA 4.0

Please read all 14 chapters before answering the survey at the end of the 14th chapter

Authors deserve your feedback. It's the only payment they get. If you go to the top of the page you will find the author's name. Click that and you can email the author easily.* Please take a few moments, if you liked the story, to say so.

[For those who use webmail, or whose regular email client opens when they want to use webmail instead: Please right click the author's name. A menu will open in which you can copy the email address (it goes directly to your clipboard without having the courtesy of mentioning that to you) to paste into your webmail system (Hotmail, Gmail, Yahoo etc). Each browser is subtly different, each Webmail system is different, or we'd give fuller instructions here. We trust you to know how to use your own system. Note: If the email address pastes or arrives with %40 in the middle, replace that weird set of characters with an @ sign.]

* Some browsers may require a right click instead