Enough Rope

by Joe Casey

Chapter 8

Days like this - days that you knew you would remember for the rest of your life - started out innocently enough, so innocently that their import became apparent only later, perhaps much later, when the events that had precipitated them fell, like dominoes, towards their inevitable conclusion.

I walked into the middle of it when I came home from work. The summer I was scheduled to leave for Northwestern, I had taken a job at Dierberg's, as a bagger and a stock boy. I liked the work well enough; it was a fairly simple job and the people were nice. I let them schedule me for as many hours as they wanted; I could certainly use the money this fall in Chicago, and it kept me out of the house. And out of Tom's reach.

I knew something was up the moment I walked into the kitchen door. Tom was at the table, leaning back in his chair, arms crossed, legs stretched out, a truculent look on his face. My mom stood at the window, looking out into the back yard; I could tell, by the subtle heave of her shoulders, that she was crying. My father sat across the table from Tom, hunched forwards, hands clasped under his chin as if in prayer, a hollow look in his eyes, a look that seemed to signal nothing but defeat.

Tom flicked a quick glance at me, looked away into space. I remarked again at how much he had changed physically in the last year. He was taller, thinner, his face more defined; the faint scruff of a beard helped with that. He'd let his hair go longer so that it hung in his eyes; all of us had gotten used to the jerk of his head periodically to get it out of the way. He had managed to acquire a kind of dangerous sexiness, in the pout of his mouth and his hooded eyes, in the way his clothes casually complemented his slender, muscular frame. Today he was dressed in a white sleeveless t-shirt and size-too-small denims that hugged his body like paint.

"What's going on?" I asked, opening the fridge, taking out a soda, cracking it open.

My mother answered only with a ragged sigh: no answer. I turned to my father, asking the same question with a look. He cleared his throat. "Your brother has, ah … has discovered what to do with the rest of his life, it seems."

I looked at Tom; he grinned back at me. "Private Thomas Keenan, reporting for duty, sir."

It took me a second. "What?"

There was another phlegmy rasp from my father. "Your brother has volunteered to go in the Army."

"You're kidding."

"What else am I going to do, right?" Tom asked. "I'm not like you , Tim." Whatever that meant.

I sat down at the table; the next thing I said slipped out of my mouth before my brain had a chance to look at it. "I thought they didn't let guys like you -" I stopped myself before the rest of it landed. My parents - if they even noticed what I'd said - said nothing.

"Guess you thought wrong, Tim." His voice light, trying to deflect with innocence what we both knew to be true.

He must have lied about it, I realized. "When do you leave?"

"Trying to get rid of me so soon?"

I stared at him. "Fuck you, Tom."

My father sighed. "Tim, c'mon …"

"Not for a month, they say," Tom answered. "But -"

"But?"

"But I'm going to take a little road trip, go see some things before I get shipped out." A few months ago, Tom had managed to pick up a used '62 Thunderbird, a convertible, bright red; no one had asked where the money had come from, perhaps because they were afraid of the answer. He had not - as far as we knew - ever held down a steady job.

Last year, almost seventeen thousand American boys did not come home from Vietnam alive. There were protests and talk of peace, but there were still plenty of victims willing to throw themselves into the maw of the American war machine … one that was steadily getting its ass handed to it by the Viet Cong.

Tom and I stared at each other for a long moment; there were so many things I wanted to ask him but could not, at least not now. I chose the safest question out of the lot. "Why are you doing this?" I asked, my voice a whisper.

And he understood. "I have to, Tim. You know I do."

I did not know it then, but I would never see him again.

Whether or not he had to, he did it. A few days after his news, he whispered away from us in the Thunderbird, gone before any of us had even gotten out of bed. My mother spent the first few days after his departure in a kind of haze, there but not. My father slipped further into stoic resignation, speaking only when spoken to, doing only that which was necessary to continue on.

Even I felt different, now that Tom was gone. I assumed he would come back to us at the end of it, perhaps a different person, perhaps not, but would again be part of our lives.

And, yet, each night the three of us sat in front of the television, watching the news from Vietnam, seeing the body counts, the explosions, the bodies themselves, a war made real by the immediacy of the reporting. My parents' generation had received their news about Korea and World War II largely through the newspapers and the radio, and although those media had done much to make the country understand the inherent horror in war, seeing it every night in your living room, in color, interspersed with the weather and the stock returns and commercials about new Pontiacs, lent a horrifying kind of banality to it.

I knew that I could just as easily be in Tom's shoes, right now. I, like all of the men in my generation, was required to register for the draft. Being in college might save me, but that alone was no guarantee.

The rest of my summer limped along lazily to its foregone conclusion: my departure for college. There had been no news from Tom all that time; we had no idea where he was - in the States or already shipped overseas; just how long did basic training take, anyway? - and his absence was nearly as full of import as his presence had been.

My parents did not know how to handle my leaving. They had both been dead set from the beginning against Northwestern and Chicago even as they understood that I had - largely through my own efforts - gained admission to a very good school. It was hard for me to imagine the three of us bundling ourselves into my father's Chrysler - its trunk stuffed to the gills with my belongings - and heading up the interstate to campus. It was harder still to imagine them arm in arm, waving - my mother crying openly, my father being gruff to mask his own unshed tears - as I, smiling bravely, already homesick, slipped into the vestibule of some ivy-covered dorm and into my future.

All of this was solved one day when my father, on one Saturday a week before I was due to leave, looked at me over the breakfast table and a cup of coffee. "C'mon," he said. "We've got an errand to run."

The errand turned out to be a tour of used car lots scattered like a line of ants along Gravois Avenue. We hunted and picked and pecked for nearly three hours until one of the cars seemed to evoke some kind of response from me (I had quickly understood that the car was for me and not for my mother) much like one particular puppy out of dozens at the pound. It was a little pale-blue Corvair wagon with a white painted top, a '64; there was something I liked about it. It was sensible, compact and economical, would be easy to park, would accommodate a fair amount of worldly goods, would be easy to service, would be mine to use as I pleased.

It was not a Thunderbird.

I watched, seated next to my father in the sales manager's office, as he wrote out a check for the full amount of the car's purchase price (he had not tried to dicker the price down) and I understood that, for my father, there were times when money was worth spending and times when it was not. I understood also that, the moment I stepped behind the wheel of that little Corvair, my life would be my own and I alone would be responsible for it.

And so, much like my brother had done only weeks earlier, I got up before dawn one day in the middle of August, showered and shaved and dressed, went out to the Corvair - I'd packed it the night before - got behind the wheel, and drove away into the brightening day. Away from St. Louis, my life here, a raft of memories, my parents, Paul, Tom.

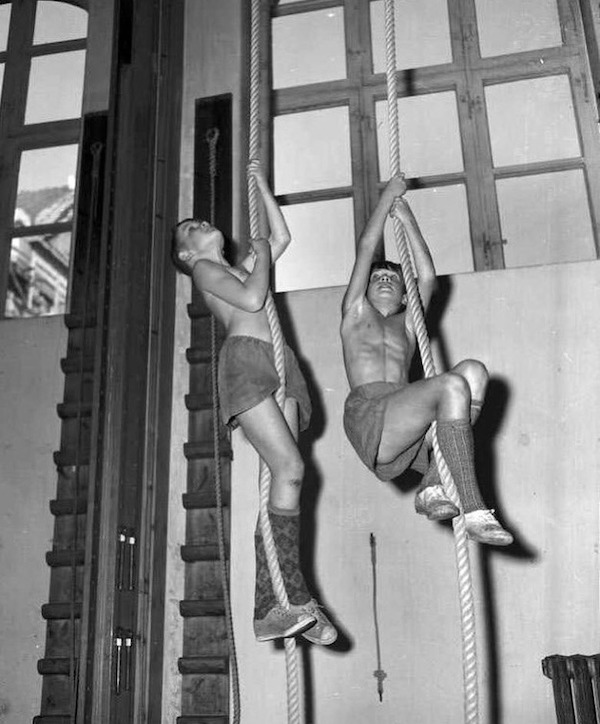

This 14 chapter story was created for the Inspired by a Picture: The Only Way is Up! Writing Challenge. The picture that inspired the story is:

Gymnastics at Ila school By Leif Ørnelund / Oslo Museum, License: Attrbution-ShareAlike CC BY-SA 4.0

Please read all 14 chapters before answering the survey at the end of the 14th chapter

Authors deserve your feedback. It's the only payment they get. If you go to the top of the page you will find the author's name. Click that and you can email the author easily.* Please take a few moments, if you liked the story, to say so.

[For those who use webmail, or whose regular email client opens when they want to use webmail instead: Please right click the author's name. A menu will open in which you can copy the email address (it goes directly to your clipboard without having the courtesy of mentioning that to you) to paste into your webmail system (Hotmail, Gmail, Yahoo etc). Each browser is subtly different, each Webmail system is different, or we'd give fuller instructions here. We trust you to know how to use your own system. Note: If the email address pastes or arrives with %40 in the middle, replace that weird set of characters with an @ sign.]

* Some browsers may require a right click instead