Passing Stranger

By Mihangel

5. Hungry shivering self

It is an uneasy lot at best, to be what we call highly taught and yet not to enjoy: to be present at this great spectacle of life and never to be liberated from a small hungry shivering self.

George Eliot, Middlemarch

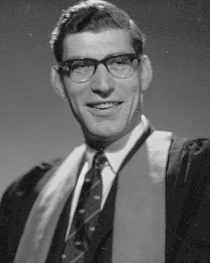

I left Yarborough, then, crowned with academic glory but cursed with a retiring nature. So it remained. I had friendships, but none deep enough for confidences. My secret remained mine. I had been gay since puberty if not before, and fifty years were to pass before I admitted it to a single soul. In this respect, most of a lifetime wasted.

The next twenty years demand little space, for in this same respect they were empty.

Cambridge followed Yarborough, with more public success -- presidency of a university society, college librarianship, prizes, first-class degree, doctorate, fellowship -- but with private failure. Yearnings remained undiminished and unsatisfied. Around me there must have been gays aplenty, but I recognised none. Years afterwards, far too late, I discovered that two of my acquaintances had in fact been gay and that one of them, whom I had known quite well, had later come to a sticky end as the victim of a gay murder. Perhaps, in the event, I had a lucky escape. That sort of world was emphatically not mine.

Cambridge followed Yarborough, with more public success -- presidency of a university society, college librarianship, prizes, first-class degree, doctorate, fellowship -- but with private failure. Yearnings remained undiminished and unsatisfied. Around me there must have been gays aplenty, but I recognised none. Years afterwards, far too late, I discovered that two of my acquaintances had in fact been gay and that one of them, whom I had known quite well, had later come to a sticky end as the victim of a gay murder. Perhaps, in the event, I had a lucky escape. That sort of world was emphatically not mine.

After nine years I wrenched myself away from the ivory tower to the nitty-gritty of extramural lecturing at a provincial university. It was a demanding life, teaching adults out in the sticks at unsociable hours of the night, at weekends and in vacations, and driving long distances in all weathers. Far more friends, inevitably, emerged from among my students than among my colleagues. Yet the semi-detached job suited a lone wolf, and on its own plane it was hugely rewarding.

Recognition in the outside world came too: seats on committees hither and yon, secretary of this body, chairman of that, fellow of learned societies. Books, articles, lectures and conference papers all brought an international standing in my subject. What scholar could ask for more fulfilment?

Yet public initiative was still countered by private inadequacy. The hermit inside -- or the prisoner -- continued unfulfilled, shy, and lonely. Vulnerability, I found, is by no means a monopoly of the young. As ever, good though my friends might be, none was close enough to be shown my inner self. Sometimes I was miserable enough to ask "what the hell's the point?" and to wonder if suicide was the best way out. Such crises were unusual, but the void of my emptiness, while it did not often keep me awake at night, was ever-present. Gather ye rosebuds while ye may, we are told. I had signally failed to gather a single one, and with every passing year it seemed clearer that there were no rosebuds for me. Nobody would fall for me now, any more than they had before. I might have bought sex - homosexual activity was decriminalised in 1967 -- but a commercial union went against all my principles, and I could supply my own modest needs. All I wanted now was someone to love.

My inner mentor, now that my public façade was established and my lack of private enterprise left him unemployed, was fading away. He had in any case been imaginary. I needed a real someone to trust, a real someone to commune with, a real someone on the same wavelength. But that someone could not be bought, or even found.

Thus for twenty years the wind blew me through my desert. Whichever way I looked, boundless and bare, the lone and level sands stretched far away. Isolation, it seemed, was my lot to the end of my days. What does it matter, I asked myself in my periodic bouts of black pessimism, if this creature called Michael, this insignificant member of the species called Man, is a misfit? Man, great lord of all things yet a prey to all, born but to die and reasoning but to err. Man, six billion strong, jostling for space with maybe fifty million other species on an insignificant planet which circles an insignificant star in an insignificant galaxy. Two hundred billion stars in a galaxy, two hundred billion galaxies in the universe.

What does it matter if one grain of sand in a desert has an odd shape? It is still no more nor less than a grain of sand. In the overall scheme of things, is not one odd-shaped member of the human race equally insignificant? Are we not all blown by Omar Khayyám's wind?

Into this universe, and why not knowing

Nor whence, like water willy-nilly flowing;

And out of it, as wind along the waste,

I know not whither, willy-nilly blowing.

In my optimism I still sometimes hoped. In my pessimism I accepted my insignificance, not with self-pity but with resignation. Inshallah, I might have said had I been a Muslim. As God wills . . .

*

The story goes that Maurice Bowra, on being told that he should not marry a girl as unbeautiful as his fiancée, replied "My dear fellow, buggers can't be choosers." Some gays no doubt marry out of desperation, some in order to conform. Neither applies to me. Nor, for that matter, can my wife be called unbeautiful; not by any stretch of the imagination.

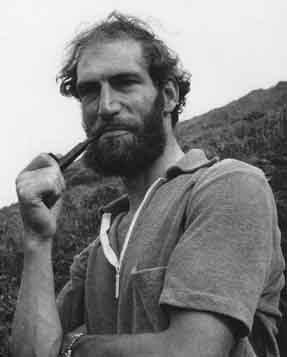

For all those twenty empty years I thought myself incapable of loving the opposite sex. I was meeting plenty of women now, and not one was turning me on. In the thirty years thereafter I have met plenty more, and not one of them has appealed. In my whole life I have encountered one woman I wanted to live with, and only one. Only with her have I found the incandescence of love. The August I turned thirty-six, Hilary appeared out of the blue, a student on a residential course of mine in Wales. At first we talked politely. By the end of the week we liked each other. At New Year we renewed contact and love began to stir. In February I went to stay with her. In March we were engaged. A year later we married. All nature wore one universal grin.

For all those twenty empty years I thought myself incapable of loving the opposite sex. I was meeting plenty of women now, and not one was turning me on. In the thirty years thereafter I have met plenty more, and not one of them has appealed. In my whole life I have encountered one woman I wanted to live with, and only one. Only with her have I found the incandescence of love. The August I turned thirty-six, Hilary appeared out of the blue, a student on a residential course of mine in Wales. At first we talked politely. By the end of the week we liked each other. At New Year we renewed contact and love began to stir. In February I went to stay with her. In March we were engaged. A year later we married. All nature wore one universal grin.

Although that was the best move of my life, never once regretted, this is not the story of our marriage. Suffice it to say that no two independent characters can live together without their downs as well as their ups. Hilary's job was tougher even than mine, and there was stress on both sides. At times we seemed like the left-handed bindweed and the right-handed honeysuckle trying in vain to intertwine. My low self-esteem has hardly helped. But the ultimate proof of the pudding . . . After nearly thirty years we are still together in strengthened harmony, with the love and friendship (at a distance now) of two great children.

The discovery that I was not wholly gay caught me utterly unawares, and gave me furiously to think. My new-found straightness now dominated my life. My gayness, built-in though it was, became subsidiary. It threatened no clash of interests, no impediment to conjugal love. But how much, in fairness, should I tell Hilary of its past, feeble though it had been? During our courtship and engagement, when we lived on opposite sides of the country, we opened our hearts to each other in letters, frequent and long. Early in this process I dropped a hint about my nature. She did not pick it up. I dropped another, broader this time. She disregarded that as well. I knew her thinking was liberal and tolerant. Had it been otherwise I could not have married her. I had a sneaking qualm that, having trusted her with everything else, I should trust her with this too. But mentally I shrugged my shoulders, and dropped it. I wish, in hindsight, that I had been bolder.

Tactile was the last thing that my family had been. I had not hugged anyone in my life, not properly, let alone kissed them properly. Hilary had to teach me. And she gave me the sexual fulfilment I needed. More importantly she gave me, as the first person in my life to whom I could talk almost without restraint, emotional fulfilment too. Or, more accurately, a generous portion of it, for while she filled most of my emptiness she could not fill it all.

Women and men think differently. Each have their own needs. Women need their bosom friends with whom they can talk about things important to women. Hilary has always had such friends, and I do not in the least begrudge it, or expect to be in on their talk. Likewise men need to talk with men. Gay men, more particularly, need to commune with friends who know gayness from the inside. Such friends I had never had. With the best will in the world Hilary, being neither male nor gay, could not fill this part of my vacuum.

To hazard a guess, though these things can hardly be quantified, perhaps one tenth of my need remained unsatisfied. Not gay physical need: that was ancient history now, and fidelity comes near the top of my priority list. What remained was the need of gay companionship. It did not nag. Not now. It simply lay dormant, as if in hibernation. My inner mentor who had faithfully held my hand in my teens and twenties had already gone to sleep as well. It seemed that his day was done.

Marriage may work marvels, but rarely miracles. While it eased the hermit out of his narrow cell, it could not change him into an extrovert. It was hard for the old dog to learn new tricks. To this day, emotions are not easy to express. Shyness, unsociability, a sense of inadequacy, persist. Parties, for instance, remain purgatorial, unless I know the others well. The sapling that starts lop-sided never acquires a natural symmetry; but marriage pruned me into a less awkward shape.

In April 2001 we celebrated our silver wedding. A few months later, irked by the growing inanities of university organisation, I applied for slightly early retirement. Research projects had piled up, panting for attention, and in that sense a full life remained full. But at last I was free to do exactly what I wanted, when I wanted.

At this turning point of my life I paused to take stock. At last I had leisure to sit back and ponder my past. Though largely content with my current lot and largely freed from my black depressions, I still deplored my youthful lack of initiative and the empty years that had followed. My gayness began to puzzle me again. It was rooted, and its leaves had unfolded, in my boyhood. The man, it always seems to me, is shaped to some extent by his childhood but much more by his adolescence. It is there that the processes lie which really matter. It was there, in my case, that the deepest mysteries lay and, yes, the greatest regrets. I began to cast my mind back, remembering, wondering, wishing. I launched into a quest.

I was not trying to recover my youth. There is little more pathetic than ageing men pretending to be boys: which is not the same as being young at heart -- no father worth his salt can escape rejuvenation by his children, and my sense of humour borders on the juvenile. What I was trying to recover was the memory of what it was to be young, back in that distant past when my make-up was shaped and set. At the same time an old desire stirred from its hibernation: the desire for a gay friend to commune with, for a friend who had come from the same place as me, for a friend who would understand what I was talking about. My inner mentor, however, did not revive. Being a construct of the imagination, his memory had faded into nothingness.

Authors deserve your feedback. It's the only payment they get. If you go to the top of the page you will find the author's name. Click that and you can email the author easily.* Please take a few moments, if you liked the story, to say so.

[For those who use webmail, or whose regular email client opens when they want to use webmail instead: Please right click the author's name. A menu will open in which you can copy the email address (it goes directly to your clipboard without having the courtesy of mentioning that to you) to paste into your webmail system (Hotmail, Gmail, Yahoo etc). Each browser is subtly different, each Webmail system is different, or we'd give fuller instructions here. We trust you to know how to use your own system. Note: If the email address pastes or arrives with %40 in the middle, replace that weird set of characters with an @ sign.]

* Some browsers may require a right click instead